David Scott, Open University

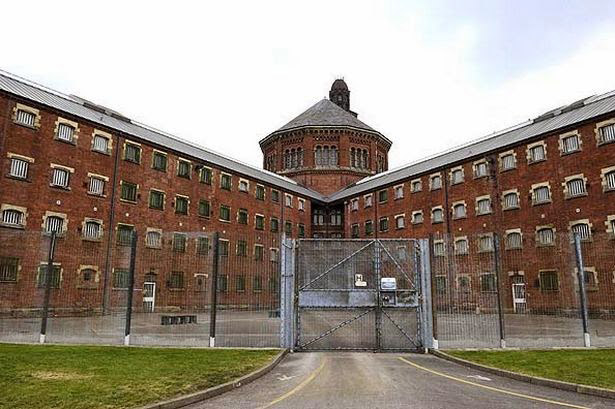

(Photo above of prisoners on social media following HMP Birmingham Disturbances – Source: ibtimes.co.uk)

Headline after headline in the British Press in recent months has placed a spotlight on prisoner violence. Prisoner violence, especially that by prisoners against prison officers, has been consistently portrayed as reaching epidemic proportions. Statistics have been rolled out again and again detailing rises in assaults on staff, prisoner homicides and general levels of interpersonal violence in the last four years. Yet much of the recent media focuses only on the physical violence perpetrated by prisoners. Whilst such violence should not be ignored or downplayed, it is only one kind of prison violence and by no means the most deadly or prevalent.

Bad Prisoners?

Violence is regarded by many people to be immoral and the perpetration of physical violence considered problematic by most people in most circumstances. Official condemnations of prisoner physical violence, from the Justice Secretary, politicians, penal practitioners and penal reformers certainly have not been in short supply in recent times, but often explanations of violence have been reduced to inherently violent prisoners who have a deprived nature / natural tendency towards violence (in other words, prisoners are dangerous, violent and irrational people who would be equally, if not more, violent on the outside). But the problem of prisoner violence, and the problem of violence within prisons more generally, cannot be reduced to an increase in the number of violent prisoners alone, if at all.

The brutal facts are that prisons are organised around the dictates of domination and exploitation. Hierarchical and hostile relationships result from an ‘unequal exchange’ between people ranked differently. These differences in status are a key generator of conflict and physical violence. Exploitation takes many different forms in the prison place, such as through the informal prisoner code or bullying. For prisoners, physical violence can be a way of acquiring goods and services, keeping face or fronting out problems. In social hierarchies there are always winners and losers, with the losers open to physical (and sometimes sexual) exploitation. Though the physical violence of prisoners is often relatively minor (with the exception of 2015, in recent times in the UK there have been only small numbers of prisoner homicides) victimisation and exploitation are routinised and part of the social organisation of the prison. But this is not the only form of prison violence.

Prison Officer Violence

For a long time physical violence by prisoners against prison officers was taken for granted as a part of prison life. With the promotion of a “zero tolerance” policy by the Prison Officer Association in 2012 this appears to have changed. However it still seems to be regularly accepted that physical violence can and will be deployed by prison officers where and when deemed necessary. Prison officer violence is also connected to the prison hierarchies. Although staff cultures differ across and within prisons, the hierarchical nature of the prison place creates an ‘us and them’ mentality. Physical violence against prisoners is sometimes viewed by staff as not only necessary but also morally justifiable, something which has been referred to by Richard Edney in 1997 as “righteous violence”. Using violence against prisoners has also in the past been used as a means of gaining respect and status as well as providing ‘excitement’ in the otherwise bleak and monotonous routine.

Prison officer autobiographies in recent years are a valuable source of information on prison officer violence. They inform us that for prison officers the location and timing of physical violence is often carefully chosen. Sometimes it takes place in concealed and isolated places where the officer cannot be easily seen; other times officers may utilise the opportunities given to them by prisoners – such as targeting unpopular prisoners during prisoner disturbances or on the way to the segregation unit or applying greater force than necessary when applying restraints. More indirectly, prison officers can facilitate prisoner-on-prisoner interpersonal violence by turning a blind eye, such as leaving the cell of a potential victim open; failing to patrol hot-spot areas known for prisoner assaults; or failing to intervene when physical violence erupts between two prisoners.

Physical violence may well be rare events in certain prisons, but this does not mean people live free from the shadow of violence. What is always present is the fear of violence. The exercise of violence can be explicit – as for example through searches; control and restraint; locking people into a cell and so on – or it can be implicit when prisoners conform because they know physical violence will follow if they do not.

Invisible Violence

There is, however, a further form of violence in prison. This silent, invisible yet potentially deadly form of violence has been named as institutionally-structured violence. The deprivations of daily prison life that restrict access to necessary life resources negatively impact upon health, wellbeing and intellectual, physical and spiritual development. Operating independently of human actions, the harmful outcomes of daily prison life have a permanent, continuous presence in the prison. Rather than being perverse or abnormal, this form of violence is an inevitable and legal feature of prison life. Prisons are places of violence when autonomy and choices are severely curtailed; human wellbeing, potential and development are undermined; feelings of safety and sense of security are weak; and human needs are systematically denied through the restrictive and inequitable distribution of resources.

A person can never be truly free in prison – everywhere they will be restricted by invisible (and sometimes quite visible) chains that place significant limitations upon human movement. The general lack of privacy and intimacy; the forced relationships between prisoners sharing a cell; insufficient living space and personal possessions; the indignity of eating and sleeping in what is in effect a lavatory; living daily and breathing in the unpleasant smells of body odour, urine and excrement; the humiliation of defecating in the presence of others are all profoundly painful and harmful.

But the harmful outcomes of daily prison life associated with poor prison conditions and crowding are only the tip of the iceberg. Prisons severe the prisoner from their previous life and relationships, whilst internal control mechanisms and security restrictions on prisoner movements – such as access to educational and treatment programmes; religious instruction; work and leisure provision – mean that prisoners lose control of their lives. Prisons are about wasting life and using up the most important thing that we have – time.

Prisons will always be places that take things away from people: they take a persons’ time, relationships, opportunities, and sometimes their life. Prisons are places which foster feelings of fear, alienation and emotional isolation. For many prisoners, prisons are lonely, isolating and brutalising experiences. Prisons are places of dull and monotonous living and working routines depriving prisoners of their basic human needs. Combined with a painful awareness of the passing of wasted time, the mundaneness of prison life can lead to a disintegration of the self and death.

Abolish Violence

The starting point is to name the prison for what it actually is – a place of violence. It cannot be otherwise. It is essential that we learn to recognise how the brutal mundaneness of everyday prison life can be so corrosive to human wellbeing. We need to make the full extent of prison violence more visible.

Prisons are the enemy of the people, not their protector. Prisons life is an unfolding human tragedy for all those caught up in exploitative and oppressive relations. Focusing on prisons as a place of violence also highlights the tensions around promoting the criminal law as a means of responding to social harms such as sexual violence. Indeed, the punishment of sexual violence has not only led to the reinforcement of state legitimacy but in the USA at least to further expansion of the penal net among poor, disadvantaged and marginalised women. The belief that prisons can be used to ‘control’ male violence and create greater safety and public protection are today key ways of legitimating the prison place.

Human choices, are of course, constrained by social circumstances, not determined by them. So we should acknowledge that many of current harms of the prison place can be challenged. Prison authorities and prison officers should be encouraged to talk openly about the harmful consequences they see on a daily basis: they, alongside prisoners, can bear witness to truth of current penal realities and should be allowed to do so without negative consequences. Whilst it is impossible to change all the structural arrangements of the prison place, there are still everyday operational practices and cultures that can transformed. Some need deprivations can be removed and many daily infringements of human dignity can be greatly reduced. Cultural changes can be made to promote a democratic culture providing first a voice to prisoners and then a commitment to listen to that voice with respect and due consideration. Finding new non-violent ways of dealing with personal conflicts and troubles in prison would also reduce the extent of physical violence and would help de-legitimate cultures of violence.

Yet prisons can never free themselves of violence entirely. Prisons will always be places of violence, but just not in the way that we might first think. Prisons systematically generate suffering and death. We must then urgently, vigorously and robustly call for a radical reduction in the use of prison. Quite simply, violence can never be used as a weapon against violence.

Permalink

I agree that prisons do not promote healthy living or change. I’d like to know what you think is the alternative to prison. I believe it starts early. We should promote adoption as opposed to care and support for pupils instead of exclusion and getting ex offenders back into work and education with decent housing. I feel otherwise the cycle will never be broken. Perhaps community orders of a sort have their place where people can put back into society. I have experience of the mental health system and I know many prisoners have mental and emotional distress for which they’re not always well supported.

Permalink

Hi Michelle – how about you have a read of this paper I did a few years ago called “visualising an abolitionist real utopia” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308745663_Visualising_an_abolitionist_real_utopia