Cornelia Gräbner reports from Germany on the grassroots community response in the aftermath of the Hanau Shootings.

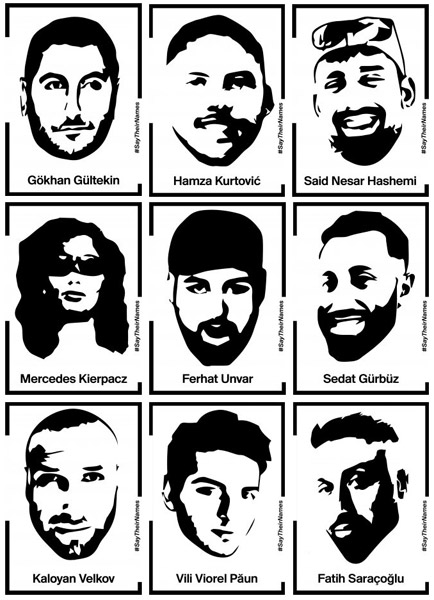

On 22nd August 2020, 5000 people were expected to gather in the German city of Hanau to remember nine people who were shot dead in a racist attack on 19th February 2020. They are Sedat Gürbüz, Ferhat Unvar, Hamza Kurtović, Gökhan Gültekin, Mercedes Kierpacz, Vili Viorel Păun, Said Nesra Hashemi, Fatih Saraçoğlu, and Kaloyan Velkov. They were between 21 and 44 years old, and they were of Kurdish, Turkish, Roma, Romanian, Bosnian, Polish, Afghan and Bulgarian descent or origin. They worked and lived in Hanau. On the evening of 19th February they happened to be out and about when Tobias R., a 43-year-old white man of racist and supremacist convictions, went out with a pistol and ammunition, determined to kill people of migratory descent.

The Shootings

On this evening, R. drove from his home to the town centre. He shot and killed three people in and around the shisha bar ‘Midnight’. He carried on to the Kurt Schumacher Square in the neighbourhood of Kesselstadt and shot dead six people: on the square; in a corner shop; and in the ArenaBar. He then drove to his home in Kesselstadt where he killed his 72-year-old mother and himself. Days previously, R. had posted a manifesto on his website. The text expressed a combination of conspiracy theories, white paranoia, virulent racism, and a desire for ethnic cleansing.

R. has been presented as a ‘lone wolf’ right-wing terrorist; but some of the media, civil society groups, and experts disagree. Right-wing extremists are usually part of online networks, and this seems to have been the case with R. also. Members of these networks use internet chatrooms and forums where fears are nurtured and atrocities are fantasised and approved of. They embrace ‘leaderless resistance’, a form of action put forward in a novel on race wars in the U.S. The idea of the ‘lone wolf’ right-wing terrorist hides the role of these networks and ignores that ‘leaderless resistance’ is a shared approach. It also hides the role of all those who create a public discourse of fear and hatred in the public space by legal means, pushing fears that white cultures, the Christian religion and white privilege are being replaced, slandering those who are part of and who defend a multi-ethnic, multicultural, multi-religious, anti-fascist society.

An Organised Grassroots Response

Immediately after the shootings, people in Hanau and from elsewhere came together for vigils and demonstrations. To create the basis for longer-term grassroots organisation, some formed the ‘Initiative 19th February’. They connected with the families of those killed. With donations, they rented a space now named #SayTheirNames, opposite the Midnight Bar. Since opening in mid-May, it has been accessible and available during COVID-related restrictions, so that those affected would know where they could find people to turn to and so that they would have a place to go to. Other organisations involved include the Frankfurt-based organisation Response, which works with those affected by racist violence and has acted as a link between the authorities and the families to channel emergency assistance, and the Hanau Council of People of Migratory Descent (Auslanderbeirat) which represents people of migratory descent in local politics.

Organisers in Hanau drew on the experience and support of civil society groups. Since the early 2000s, members of civil society across Germany have stepped up concerted organisation, mobilisation and education against the extreme right. Civil society groups with people from a range of ethnic origins rose to the challenge of working in a climate where state institutions and politicians downplay the impact and seriousness of racist and extreme right violence. They identify, research, analyse, call out and oppose the actions, attitudes and policies of the extreme right, and of those that shield or support them. They counter them with multiple tactics. Among those are creating public awareness; research and exposure of right-wing groups, and networks of institutional and cultural complicity; training in discursive tactics; direct action; memory and memorial work; public mobilisation, and education. Now, they set the standards for dealing with the extreme right, and authorities and the state need to live up to these standards.

A series of failings and a little help: The Authorities

They rarely ever do. In the case of R., plenty of warning signs were not heeded, let alone acted upon. R. had his firearms licence renewed in 2019 by authorities in Hanau. Though they knew that R. had previously lived in Munich, they did not check his record with the local authorities – if they had, they might have learnt that R. was being investigated for possible arson and offences related to illegal substances, and that he had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. R. had also insistently raised claims with the police in Frankfurt and with the General Attorney about being persecuted by a secret organisation. The police and the General Attorney’s office did not take him seriously, and did not pick up on the fact that many of the narratives and motives R. drew on are disseminated by right-wing conspiracy theories.

The police in Hanau have been accused of a slow, inadequate and insensitive response to the attack, and for the lack of prevention. Youngsters who met at the Kesselstadt Youth Centre reported that before the crime they had called the police several times to report that a hooded man had entered the premises and threatened to kill them. The police treated the youths as if they were creating a nuisance. On 19th February, Vili Viorel Paun, one of the victims, tried to call the police four times but did not get through. The fire brigade – who are stationed on the other side of town – arrived on site before the police. Police came in a patrol car, not with a special squad. According to eyewitnesses, the officers did not leave the car and enter the site of the shooting until ten minutes later, though victims could be heard calling out from inside. The special squad arrived at R.’s house about one hour after the shootings, though eye witnesses say that they gave the police R.’s licence plate number immediately – at that time, R. had several rounds of ammunition left and could have continued his rampage.

During the night of the attack, authorities did not inform family members of the death of their loved ones until the early morning of the 20th, leaving them in anguish. Post-mortems were carried out without consulting the families; post-mortem violates Islamic religious customs. Families received emergency financial aid; however, this dried up quickly, especially as many of them have been signed off work since the attacks and rely on sick pay. Some of them wish to move within the city, as they live in the immediate vicinity of the sites of the attack and have to look at them every day; however, the city has not been forthcoming in helping them to find new accommodation.

The authorities say that there were no legal grounds on which further enquiries could have been raised regarding the renewal of R.’s licence. In a meeting with family members and supporters in mid-May, the minister of the interior of the federal state of Hesse, Peter Beuth, insisted that the police had done an excellent job. Neither of these responses are appropriate to right-wing violence of leaderless resistance, nor do they reach the standards set by civil society. So far, none of the authorities have apologised.

‘Their death has to be the start of something new, of schools without racism and of a living together where we all have the same rights.’

These are the words of Serpil Unvar, mother of Ferhat Unvar, who was killed at the age of 23. On the evening of 21st August at 7pm, the city government of Hanau withdrew the permit for the demonstration planned for the 22nd. They cited the rise in COVID-19 infections and public health and safety as reasons. For weeks, organisers of the demonstrations had been developing a hygiene plan, in collaboration with the city’s health authorities. They wanted the event to be held safely and in the spirit of looking out for each other.

By prohibiting the demonstration, the authorities withheld from the families, the friends and the community of those killed, the immediate experience of feeling themselves held, supported and shielded by 5000 people who were committed to making sure that none of this would be forgotten, and that it would not happen again. The authorities withheld from the people who wanted to attend the demonstration the opportunity to bring and share their energies from different parts of the country, and to take with them to their different places the intensity of sharing time and space with the families, the survivors and each other.

The short notice of the city’s decision did not give the organisers enough time to launch a legal appeal. Instead, they negotiated permission for a smaller event with 249 people, so that families, friends, community members and allies could give the speeches they had prepared. Across the country people worked through the night to set up smaller events in 50 German cities, as well as the infrastructure for a live stream of the speeches so that the pain, the grief and the anger could be heard and responded to, so that the ‘something new’ that Serpil Unvar spoke of can come into being. As the authorities put obstacles in the way, people remain committed to making Serpil Unvar’s vision a reality: ‘When we have achieved this, I will stand by my son’s grave and I will say: This was your struggle, and you won it.’

**Update**

Since August 2020, the president of Germany held a meeting with survivors of the Hanau attacks and promised assistance. Organising efforts have also continued. In October 2020, members of the community that emerged around the Hanau attacks spoke at the Festival of Resilience in Berlin, organised by Jewish organisations to celebrate the community’s resilience in the aftermath of a right-wing attack by another so-called ‘lone wolf’ , on Yom Kippur of 2019, on the Jewish Synagogue in Halle and a local kebab shop, during which two people were killed. Another speaker at the Festival of Resilience was Faruk Arslan, who had also spoken at the Hanau event and who lost his mother, his niece and his daughter to a racist arson attack on his house in Mölln in 1992. Survivors and their allies are joining forces, across communities, religions, and throughout the country.