Nerve contributor Lisa Worth has written a feature on Dylan Thomas and Laugharne.

In 1914 Dylan Thomas was born into a comfortable suburb of Swansea, which he described as “an ugly, lovely town crawling, sprawling by the side of a long and splendid curving shore.”

His childhood was happy. Carefree days were spent at Cwmdonkin Park and long holidays at Fern Hill Farm, the home of his aunt.

Both places afforded him a sense of freedom and possibility, themes that recurred throughout his work, although often with added mournfulness at the loss of them in adulthood.

Fern Hill perfectly captured this:

“Time held me green and dying/Though I sang in my chains like the sea”.

His father taught literature at his school, but it was no deterrent to Dylan who bunked off and wrote poetry instead. His only incentive to attend was editing the school magazine, where his early poems appeared, which led to him joining the South Wales Daily Post.

But his employment was brief, and offered little of interest for him other than drinking opportunities while story – hunting around the docks. He was sacked and so began his freelance career as a writer.

The poet’s output was prodigious in his teens, but became erratic as he pursued an itinerant life bouncing between temporary homes. It was his years in the fishing village of Laugharne, Camarthenshire, where his best work was written.

Dylan Thomas and Laugharne are inextricably linked. The village peters out to the Grist, an open area where once stood a mill. Here, land makes way to salt-marshes that reach out into the estuary of the River Taf, the colossal 12th century castle looking on and dwarfing the brilliant white Boathouse that was the poet’s home.

There’s something about it that’s reminiscent of Constable’s Haywain, or Vaughan Williams’ Lark Ascending, and it offers a quietude seldom found in our modern world.

The pace is unhurried and the late summer light ethereal, which casts a diaphanous handkerchief over the curlews, their delicate calls hanging on the air.

It featured in Poem on his Birthday :

“Flounders, gulls, on their cold, dying trails/Doing what they are told/Curlews aloud in the congered waves/Work at their ways to death.”

Breathing is easy here and the purity of the air encourages clarity of thought, and it’s that environment that lifted Dylan Thomas to write with a lyricism that removes the need to understand every word. The emotional connection doesn’t depend on a literal interpretation.

His word – pictures conjure up vivid imagery, at once inducing a sigh of calm and the prick of salty tears.

But the writer’s adult life didn’t match the happiness of his youth, and his poetry expresses this.

His work lingers around themes of longing and lost innocence, and the accelerating march of life – to – death.

He draws upon the Welsh concept of “Hiraeth” – the idea that something is missing, which is indefinable and unrecoverable. And this inner conflict manifested itself physically too.

Experts have suggested that today he may have been diagnosed with phsychosis, and his marriage to Caitlin Macnamara (herself at odds with the world), with whom he had three children, was tempestuous and violent.

Alcohol fuelled their relationship from both sides, and likewise infidelity. Unrelenting poverty made what now looks like a quaint seaside home something more akin to slum – living, as even at his height he was heavily in debt and forever penning begging letters to friends and contacts.

And yet, against this dysfunctional backdrop, his most well known work – Under Milkwood – was created. It’s a “play for voices” that tracks 24 hours in the village of Llaregub, drawing on the idiosyncrasies of the residents.

Although Llarergub is fictional (it reads “bugger all” backwards), it’s widely accepted that the piece is based on Laugharne. A village that Thomas described as “the strangest town in Wales” which, nonetheless, became his home for his final years.

There was some ignominy around the death of Dylan Thomas in 1953, as it came close on the heels of his own admission that he’d drank 13 straight whiskies.

Drink played a part, but pneumonia and respiratory illness were also cited as the causes of death, and the highly polltuted smog of New York could not have helped the lifelong asthmatic. He was just 39.

Dylan Thomas could be considered a modern era Romantic poet. At a time of rising fascism and racism, he was well known as left- leaning and showed an interest in Marxism. But it played no part in the aesthetic of his work.

His love of Wales rings through his work, but he abhorred the idea of nationalism, and it’s counter-intuitive that the most famous Welsh poet never spoke Welsh (although that was more likely due to the area being highly Anglicised then.)

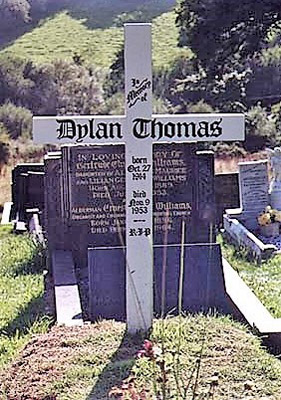

His passing is marked with a simple white cross in the graveyard at Laugharne, but his work lived on to influence artists coming up behind him.

John Lennon insisted that he should be depicted on the cover of the Sgt Pepper album, and Bob Dylan has regularly referred to him as an inspiration.

It’s interesting that the issues permeating through the life of Dylan Thomas – political tension, the rise of Populism, alcohol abuse and mental health – are red hot themes of discussion today. Even his visceral need of green space, and the toxic city air that may have hastened his demise, resonate with those of us in the 21st century.

His work may offer a distraction from our modern malaise but it’s of greater value than pure escapism. It can help us to understand our role in this daily scrum.

Encapsulated in the poet’s own words: “A good poem is a contribution to reality.”

Permalink

Lovely article and tribute don’t know how I missed this