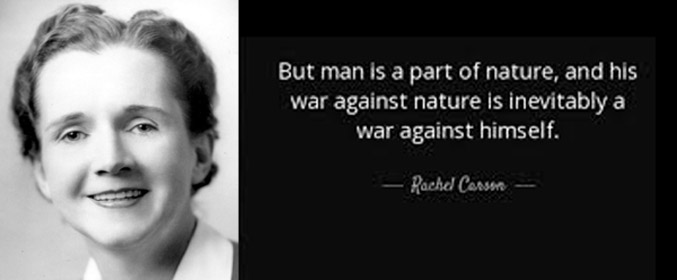

(Photo credit: learning-history.com)

No history of the modern environmental movement would be complete without Rachel Carson. Sandra Gibson demonstrates how she combined scientific rigour with empathy to challenge the anthropocentric status quo.

Rachel Carson is well-known for her pioneering endeavours as an ecologist. Her seminal publication: Silent Spring (1962) inspired the modern environmental movement. What made her so crucial to the development of biology and ecology was that she was able to combine tenacious scientific scrupulousness with a lyrically empathetic sense of the way everything connected in the natural world. This insight led her to challenge the attitude that the human species had dominion over nature, which gave the right to interfere, exploit and control. Her empathy for everything living, which led her to challenge the anthropocentric paradigm, permeates her writing about the creatures and habitats she studied. This is an extract1 from Undersea2:

“The young eels first knew life in the transition zone between the surface sea and the abyss. A thousand feet of water lay above them, straining out the rays of the sun. Only the longest and strongest of rays filtered down to the level where the eels drifted in the sea – a cold and sterile residue of blue and ultraviolet, shorn of all its warmth of reds and yellows and greens. For a twentieth part of the day the blackness was displaced by a strange light of a vivid and unearthly blue that came stealing down from above. But only the straight long rays of the sun when it passed the zenith had power to dispel the blackness, and the deep sea’s hour of dawn light was merged in its hour of twilight. Quickly the blue light faded away, and the eels lived again in the long night that was only less black than the abyss where night had no end.”

Choosing a non-human perspective, Rachel Carson writes from within the consciousness of young eels who inhabit a specific part of the ocean between the “surface sea” and the “abyss” and concentrates on their perception of changing levels of light. What is communicated is how unlike our own experience of sunlight this light of the marine depths is, and how unlike our own day and night that of the eels is. Living at a level where only the long rays penetrate, light is experienced as blue: either as blue and ultraviolet, or for a brief one twentieth of the time, “a vivid and unearthly blue” – a sort of daytime when the sun is at its zenith. What is tremendous about this writing is that it challenges our own views of reality by offering a different one, at the same time that it unites us with that different reality through a common experience: our sun, the star without which none would exist. How insightful is her reference to, “the abyss where night had no end” – the lower depths of ocean – because in evoking this chasm, she is awakening our primitive human fears of such a place, which is the normal habitat for some sea creatures. The writing of Rachel Carson is not merely descriptive, although in this she is meticulous, it is also experiential and poetic.

References:

- Cited in an essay, “Two Hundred Years of Blue”. www.brainpickings.org

- Undersea was originally a brochure for the Fisheries Bureau but what she wrote was so poetic and so unprecedented that her supervisor said it couldn’t be published as their official government report – so he suggested The Atlantic Monthly. This was in 1937.