Compiled by Bill Hunter, edited by Ritchie Hunter

Published by Living History Library 2017

AGAINST CAPITULATION – Something to be: Harry Constable, The Dockers’ Hero.

Review by Minnie Stacey, August 2017

This compilation of Bill Hunter’s many taped recordings of Harry Constable some years ago, brings Harry’s own voice through the pages. It’s a powerful narrative as lived, so vivid with his community, his developing sense of injustice and the dock workers’ struggles. No virtual reality headset is required, the blinkers are off this story set in an earlier version of our world where the revolutions of the production cycle have craven spurs for profit.

Born in 1916, Harry recalls growing up and his journey in social and political awareness, with a particular focus on the fifteen years following the Second World War when thousands of Dockers did not want to return to the working conditions of the 1930s. An exploitative, controlling capitalist system with the cruel mercenary minds it sets up and the struggle for elected worker representatives to oppose this, is the context of the book. Harry minded, he saw through it all and used his ability to lead in organising fellow workers to fight against the barbarity of being born into conditions akin to slavery.

Like his fellow Marxist-Trotskyist friend Harry, Bill Hunter never compromised his beliefs and support for the industry of workers. As with his book about the unofficial leadership and struggles on the docks (1945-1989) ‘They Knew Why They Fought’, compiling Harry’s memoirs stays true to Bill’s not following top-down prescriptive ways of academic writing. This actual working class view and knowledge allows us to understand our collective history as part of the dialectic which led us to where we are today. It’s a weapon of truth in our continuing battle against leaders selling out and enabling a cutthroat establishment.

Bill introduces Harry as a prominent, unofficial Dockers’ leader in the 1940s and 50s with particular support in London and Merseyside. He had a national reputation as a principled fighter who galvanised rank and file dockers and other workers to act in solidarity. Constable had a natural ability to speak, to write and build leadership from the ground. Bill quotes John Cavanagh who was chairman of the tally clerks’ Joint Advisory Committee in the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) in 1975 declaring Constable to be “so eloquent and able to think in depth on all industrial problems”. He was up against a status quo of employers, government and union bureaucracy, effectively a cartel defending their interests against improving working conditions and increasing wages.

Dockers knew strikes were acts of war, part of the class struggle in a vicious, arrogant system where Labour leaders were also the class enemy. The Labour government used troops on fourteen occasions between July 1945 and October 1951 to break strikes on the docks, during which there was a massive injury rate among soldiers due to what the dockers called their lack of ‘docksology’. The skill of so-called unskilled work meant dockers were used to solving the problems of handling diverse cargo such as horses, sugar, sticky rubber and even yachts. Fellow union leader Bert Aylward and Harry were against nationalisation in 1947. With the backdrop of being told by a Labour minister that workers did not have the ability to control their industry when they ran everything, nothing short of national workers’ control would do.

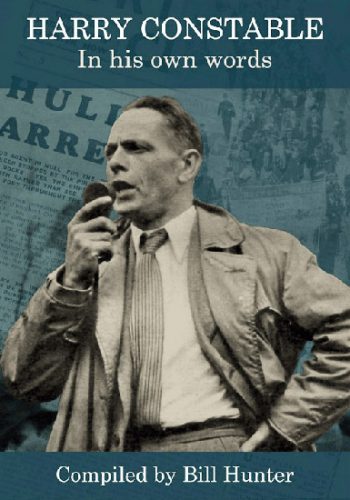

In his foreword, Bill’s son Ritchie Hunter writes how Liverpool singer-songwriter Alun Parry gave him the impetus to finish the book after his Dad died, with his song ‘If Harry Don’t Go’. We see Harry speaking into a microphone on the cover, which was designed by Paul Hunt who is part of Liverpool’s grassroots Nerve Magazine collective. It’s Harry addressing dockers after his expulsion from the TGWU in 1950 for upholding the principles of socialist trade unionism. Leading up to his arrest in 1951 with six other ‘unofficial’ leaders under wartime regulation 1305 for inciting men to strike, Harry said “We are workers, and we expect to be arrested because that’s the way capitalism works to shut you up”.

This book isn’t a dry political text, it describes the community Harry came from. The rotten rentier accommodation they were forced to live in, their cheek-by-jowl proximity, the streets alive with chatter for all to hear, the hard-drinking and dispute settling – gritty with fights, the escapism of the music hall, their sheer guts. I first dived in at the start of the dazzling and heartbreaking early chapter ‘One particularly exciting day in my life’. There’s a taster clip of Harry’s taped, poetic opening to this at www.billhunterweb.org.uk and Liverpool’s Nerve Radio will be releasing chunks of Harry’s spoken history.

Over a century the dock authorities had grabbed and walled off land. Three generations of Harry’s family worked on the docks, and workhouse-fearing Wapping had bred convinced trade-unionists and Irish-Catholic spirit towards socialism and against discrimination from work. Harry’s mother gave her children sulphur baths and painted deadly poison on bed legs to kill vermin. The appalling death rates of the time only began to change as the establishment faced an upsurge of strikes and revolt.

Harry’s young energy shines through the poverty and hardship. Strikes or lockouts meant children were “all shrewd and up to scratch” in the competition to earn a living, so boys scraped markets for scraps to supplement meals at home. Through the recording, as well as recalling the marvellous time he had playing in a very exciting but dangerous landscape, Harry retrospectively recognises the dreary situation and lesser freedoms of girls being under stricter family control and domestic duties. In Harry’s world women are strong – the main carers and counsellors, handlers of everything day-by-day, exhausted and dynamic with innovation to feed and clothe large families. A wage-earner lying in bed was a luxury no family could afford.

Constable’s path to leadership began with recognising the controlling components of capitalism at school, where learning meant bags and bags of patriotism and weals to punish schoolboy misdemeanours. He became boisterous and rebellious, and cottoned on to a puritanical streak running through officialdom. His mother prompted early lessons in how to organise when she would make a stage, gather and direct her brood in parts for plays and stories she made up.

Harry’s socialism is clear in this nicely spaced-out mass of peopled photographs and words. He’d attend demos and listen to left-wing orators with his father. As a child he was among thousands on the march to free future Labour Party leader George Lansbury and other Poplar councillors who went to jail with the slogan “Better to break the law than break the poor”. Beginning work Harry learned which books to read from older dockers, including Mikey Leer who told him to digest what they had to say and “learn what the struggle was about at the point of production, not from the platform”. He joined the Young Communist League and later aligned himself with Trotskyists and anti-Stalinists. He attended classes in working class history and socialist theory, learned about party politics at the Independent Labour Party and the IWW, delivered the Daily Worker, and fought Mosley’s fascists with his fists. When Harry joined the Sappers in 1939 only the accents of his fellow recruits, mostly miners, differed. He found himself up against and even jailed by the class enemy in the British Army as well as being up against Hitler.

Being “on the stones” in the zero-hours of early morning waiting to be picked for work, fear of unemployment, blacklisting, low pay in being squeezed for mammoth profits, hunger, long hours, compulsory overtime, dangerous work, robbery of rights, the fight for ideas, the stench of filthy un-useable toilets, lunatic bully-bosses, the maintenance of decasualisation, retirement issues, sectoral and international solidarity – all called for industrial action and Harry’s leadership came from the ranks against the dead weight of officialdom. He was inspired by Bert Aylward, a class-conscious, socialist, ‘unofficial’ leader. Described by a fellow docker as “one of the hardest working men”, whatever the struggle Bert could easily explain the essence of it to thousands of workers.

Unofficial port-worker committees were born out of the men’s experience of a stagnant, dictatorial TGWU. In his 1958 Labour Review pamphlet ‘Hands Off The Blue Union’, Bill Hunter writes that the TGWU official machine was “quite generally detested by the dockers”. With TGWU officials sitting on Dock Labour Scheme boards in cahoots with employers for disciplinary action, the men knew the closed shop only guaranteed union membership for those seeking work in line with the employers’ vetting system. Unofficial strike action was their only option. Indignant and frustrated, ten thousand men left the TGWU between 1954 and 1955 to join the ‘Blue Union’, the National Amalgamated Stevedores and Dockers (NASDU).

Editor Ritchie Hunter’s added appendices capture Harry and fellow workers’ memories of straightforward, principled leaders demanding justice – including Albert Timothy who had the extra ability to even entertain huge crowds like a comic. There’s a section on the anti-left-wing Moral Re-armament Movement (MRA), with its creed of getting workers to be “unselfish” towards employers. It succeeded in buying off one of Liverpool’s unofficial docker leaders with luxury and lies.

In the spying, Mass Observation section we hear the disconsolance of a docker walking to a meeting saying “You gotta be a wage-slave from the time you’re born to the time you die”. There’s a speaker’s call for political leadership from the brilliance among the masses, and an appeal to dockers to get information straight from committees to bypass the lies and sensationalism of the press against the Dockers’ Charter strike of 1945. There are snippets from surveillance records of Harry, Bert and other leaders’ speeches and overheard comments. Alive with atmosphere, the crowds understood this was a fight for the whole working-class of Britain. There’s laughter, wild applause, stomping, sighs, muttering, cat-calls and hostile yells.

The appendices also re-publish articles penned by Harry. In the 1951 Portworkers’ Clarion he latches onto the Leggett Report’s irritation with docker solidarity and therefore its bias against them. Re-printed from ‘The Socialist Outlook’ of May 1953, gleaning knowhow from history Harry looks back at the Great Dock Strike of 1889. His August 1957 piece ‘Now Let’s Learn The Lessons Of This Defeat’ is an analysis of the Covent Garden and Port of London stoppages current to that year. This was a defeat by the employers and Tory Government, assisted by Stalinists and the bankrupt reformist leadership of trade unions “ready to force the rank and file to accept unwelcome and ominous agreements, worshipping before the altar of procedure”. Harry’s appeal is still urgent today – the need to separate genuine leaders from phoneys.

The TGWU’s practice of trying to suppress working class solidarity failed when the men permitted an expelled Harry to work alongside them without union membership. Leadership to him was never a lever for privilege. Having left the CP at the start of WW2, he was never in dispute with Communist Party members either but with their leadership, in particular for its treacherous role in opposing a NASDU recognition strike of 1955. Constable calls out the CP leadership strategy to stay in and democratise the ‘white’ union, the TGWU, as false and a tactic to lift the ban on Communists holding office purely to advance themselves in the union hierarchy.

Reading this compilation, one comparison with grassroots leadership that strikes me is John Rees discussing his book ‘The Leveller Revolution’. He describes how the rank and file of many regiments of The New Model Army elected their own representatives, then known as ‘agitators’, in the English Revolution of the mid 1600s.

Representative organisation and leadership by, from and for the grassroots, is what comes through Harry’s voice. The turgid betrayal of diktat bureaucrats at the top of trade union organisations must not be forgotten. Like the real history in Bill and Ritchie Hunter’s work, ordnance-survey maps of the treachery in working class struggle are much needed in a ratcheting economic system where too many unions have taken on the competitive business/insurance company model. Their top-down pursuit of the bottom-line comes at the enforced expense of internal democracy.

As with direct action, this history of honest, grassroots leaders able to communicate the simple truth to the many inspires us with the courage and solidarity to stand up against a no-less cruel capitalist establishment today. Go to the book – it’s jammed with character and fleshes out the political skeleton sketched above. With an ill-gotten rich centre-ground patently gobbing-up smug gluts of self-serving biographies, Harry’s posthumously-published perspective gives us all something to chew on.

Harry Constable – in his own words (Isbn 978-0-9542077-5-5) is available from all good bookshops, or ask your local library to stock it.

For further information on Bill Hunter and his work visit: www.billhunterweb.org.uk – you can also order the book from Living History Library via the site.

Hear a taped clip of Harry Constable: www.billhunterweb.org.uk/books/harrys_special_day_ontape2a.mp3

‘If Harry Don’t Go’ by Alun Parry youtube.com/watch?v=A5QD76tKhX8