Sandra Gibson reviews a compilation of quarantine creativity by 50 people: a concept from photographer Chaz Rudd who compiled and designed it, with proceeds going to MIND charity.

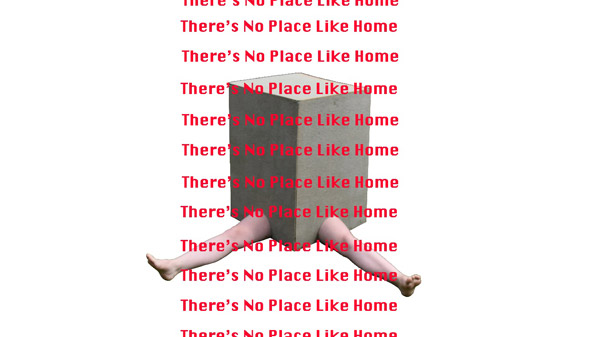

The title, There’s No Place Like Home, once a sentimental Victorian cliché, takes on new life in the context of the Covid 19 pandemic. The front cover by Emily Hulme (image above) shows a box with two legs extruded: constraint combined with a feeling of willful escape. Charlie Brazier’s back cover, with its expletive-strewn floorplan of the place of confinement, expresses the angry tedium of lockdown. So, what’s between the covers? How has the experience of being in a limited environment impacted?

Amelia Rudd’s charming, illustrated extract from Cinderella by Max Ellenberg and Niamh Sharkey, reminds us of waiting for the Fairy Godmother Government to give permission for whatever represents a ball, but now the clock has struck midnight. As we enter another peak of virus intensity it’s interesting to look back at the range of responses to the long spring and summer of the first phase.

Compulsory leisure for all but key workers meant that home and garden became a focus, and this produced a variety of reactions. With the repeated phrase STAY HOME, some sexy, sumptuous, imagery, and a strong presence of passionate red, Amy Crozier’s magazine style pages offer glossy-lipped seduction, not just of the bedroom but of the kitchen, because who can resist a yellow blender? Abbie Ozard’s* photographic study TV KWEEN is pinkly luxuriant, the reclining figure making a strong horizontal statement, while Charlotte Grocutt’s line drawing of a nude suggests that both figure and bedding are becoming part of the same! Curlymouth’s album cover for Magpie’s Nest offers the witty enticement of tree-house home-working, with additional spliff. The openness of tree-top living upgrades confinement to comfiness or perhaps it references the spaciousness of the creative mind.

TV Kween @abbieozard @another_situation @richturvey @charudd

TV Kween @abbieozard @another_situation @richturvey @charudd

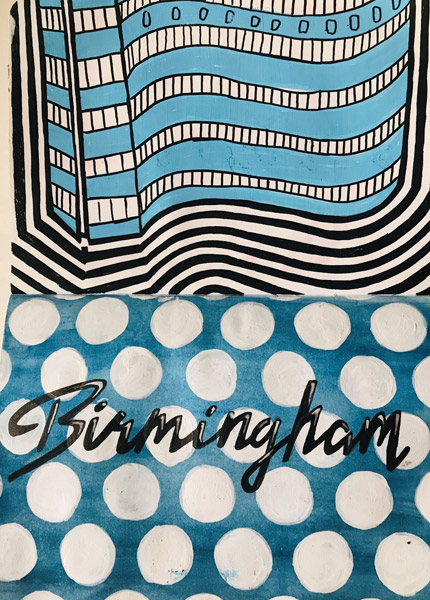

Further glimpses of domestic living are reassuringly “ordinary” such as Conner Dixon’s sequence of textured photos in a setting of trees and blossoms, though the siblings’ garden-living tent also evokes biocontrol, in our present context. The pervasive greenness in this compilation emphasises both the importance of having a garden and the deprivation of not having one. Eleanor McDonald’s circular embroideries are set against a garden background; Claudia Farmer offsets the vertical and horizontal lines of a multi-storey building with grass, spring bulbs and a tree; Holly Bazley places her subjects amongst texturally interesting greenery; Kinsey has a background of fences, shadows and bushes. There are floral celebrations too: Holly Stephenson involves floral fabrics with flowers; Akash Waqar Ali uses white flowers to surreal effect; Kayleigh Lowe enhances contrasting colours in her flower portraits and Libby Pratt’s photograph of the pristine beauty of the moon incorporates silhouetted trees and blurred, close-up foliage. Charlie Brazier’s golden-hour portrait of a person in a field becomes more significant when we notice their school sweater – school being restricted for the majority – whilst Lena Schaack’s emphatic and poignant photos of windows with toys looking out surely reference the stay-at-home children, and their possible lack of outdoor facilities (the pictures are devoid of vegetation).

If one regards Sorrel Higgins’ GIRLS ARE AWESOME photographs as a diptych, the message of limitation is unmistakable. One is in colour and its subject is as much the expanse of mid-blue summer sky (two thirds of the picture) as the subject in the tee shirt. By contrast, there is a black and white photo of the subject with a sheet hung in front, creating a barrier: claustrophobia amplified by a hedge. Libby Pratt’s humorous study of someone sitting on grass, with their trainer thrust towards the viewer, has a sense of containment which is less bothersome, more subtle. The figure is in a globe of ordinariness (grass, trees) but encircled by darkness (blues, black, brown, a hint of rainbow). Not frightening darkness – more about the world outside our own domestic or global sphere.

The book ends reassuringly with a dog sniffing grass. Kayleigh Lowe’s photograph takes on a new significance when you remember dog walking was the escape clause! The virus has created new resonances and the more you peruse, the more you realise that the collection encapsulates a long summer that is not quite what it seems.

Take Holly Stephenson’s summery portrait with floral prints and flowers: spot the unfamiliar accessory. Take the soft-focused photograph of bluebells by Libby Pratt. It surprises by not being a conventional springtime scene: the flowers are photographed big, are dramatically set against a black background, and brightly lit as if on stage. Lola Primrose has also produced some theatrically lit studies of flowers. Take Chaz Rudd’s apparently typical still-life photo of a garden table with a white cloth, vase of flowers, drink on a crocheted mat and a cake in a box – all set against a buttercup lawn that looks as if it’s plucked from a mediaeval book of hours. So far so English Country Garden but just look at the product placement: this is not just any cheesecake but Quarantine Cheesecake and beside it a knife so long it doesn’t fit the picture frame. There are other concerns: is that lemonade or absinthe? Why is the flower arrangement uneven? Are there two tablecloths? These micro-disturbances all add up to Agatha Christie territory. What clinched it for me was the old-fashioned quality of the colour-film. This photograph, with its nostalgic subject matter, retro colour tones and out of joint details, cleverly conveys the essence of 2020’s summer of leisurely unease.

Sometimes the feeling of unease is pronounced. For Thomas Gallimore Barker (Boredom’s Edge) it is more anxious, more uncomfortable, more difficult to adjust to: “Swatting a dead alarm at 3AM out of reflexive memory”. Nathan Langman’s photographs of buildings without people project encroaching darkness, created by shadow on sunny red brick, or disorientation signified by a tired old signpost, some of its letters missing – like the incomplete instructions from our government. Karen Humphries’ untitled poem counterbalances the lack of coherent strategies (“with this was no textbook”) by using a strong rhyme scheme. In Ghost Town Christian Haywood mentions rules not well founded: “a predetermined path not to be deferred by evidence’s plea”.

Another Nathan Langman photograph is more surreal in its foreboding: doors or gates placed in a green space which is deeply and strangely shadowed, a feeling echoed in Adriana Szczerepa’s untitled poem about loneliness, separation and the shadow of death: “waiting becomes a game we play with death as he hovers above each one”. There is an echo of this in the plane/bird configuration of the album tracks for Curlymouth’s Magpie’s Nest.

More optimistic, though, is Lottie Morton’s plan-like drawings of enclosed objects on a background of exercise book lines: bowls, rocks, crossword puzzle, chequered flag, star fish, daisies, amoebic shapes, and lines with hubs. Does this express the randomness of home-schooling? Do the enclosures refer to social bubbles? The mind extrapolates. What has seemed childlike has more subtlety: there is some deliberate obscuration – words written by an old-fashioned typewriter (so that sometimes part of a letter is missing) can be discerned. The treasure – the poetic writing – emerges from the map.

The unease can be more dramatic. Brendan Russell’s diptych: in colour and in monochrome, diagonally portrays three figures, the middle one a composite with dog and devil characteristics. The incomplete meme WHAT FUCK presumes we will supply the “THE” and the question mark because it’s our collective response to information about the virus, of which the hybrid creature is a manifestation. Maybe. The devil motif recurs throughout this collection, with some close emphasis on the mouth area. Casually glanced, contrasting drawings by Osragli Elezi have the letter J; glanced again it is also a forked tongue emerging from a mouth, combining the notion of the devilishness of the virus with the idea of false news and lying, which has been such a feature of daily briefings.

Eve Gittins’ devil’s head is made terrifying by her specific use – inside the ears, the eyeballs, the mouth, and long tongue – of red against bone grey. Costanza Musto has photographs of a young person wearing a toy crown with their tongue out, or messily eating. The most telling thing is the recurrence of the crown – or corona – though. Sam Kuchvara has photos of screen shots, dramatically combined with areas of black, of someone kissing a crucifix and someone placing a religious icon next to their mouth. In times of plague people traditionally turn to religion; the question is, do we devour religion or is it that we devour icons, religious or secular? Kelly Quinzel’s excellent line drawing of a mouth emitting snakes shocks by having no pupils in the eyes. In her black and white illustration, Jessie Stansby has another devilish being with no eyeballs and a long reptilian tongue wrapped round a tree which has a heart-shaped apple. This surely references the Garden of Eden – the beginning of everything being the fault of Eve – and there has certainly been some scape-goating during the pandemic, though mostly racist and ageist. Eleanor McDonald’s bold, circular embroidery of a toy snake head with small red hearts for eyes and a prominently dangerous tongue and teeth effectively juxtaposes the cuddly toy idea with danger.

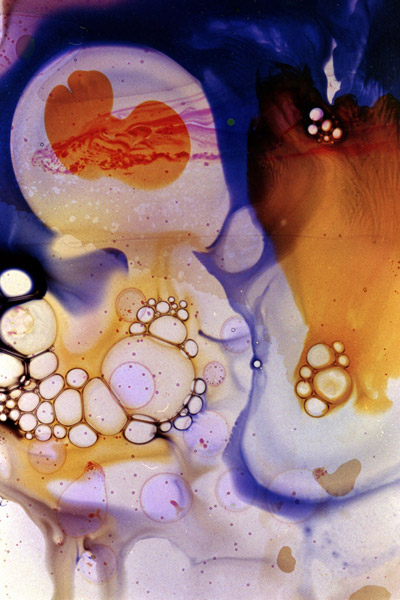

Some artists have not embraced such primal gothic horror but nevertheless express a feeling of alien life. Drawings by Kelly Quinzel show pervasive octopuses and a stereotypical space craft with a beamed-down alien. Carlos Baselga’s beautifully coloured pieces have an otherworldly quality of microscopic life.

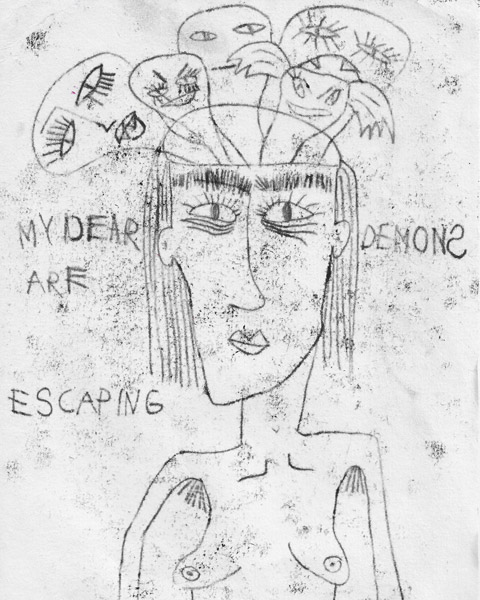

Molly Richards’ closely focused textural studies of daily life create an unfamiliar world “within the rituals of the everyday” by going beyond the boundaries of the recognizable into abstraction. Adriana Szczerepa’s drawing, which announces MY DEAR DEMONS ARE ESCAPING, is psychologically ambiguous because reptilian creatures coming out of the top of one’s head are pretty scary, but on closer examination their eyelashes make them slightly sweet – like Eleanor McDonald’s embroidered snake and Rebecca Johnson’s picture of a lovely cat in an aggressive HIGHLY DANGEROUS MOTHER FUCKER sweater.

Similarly ambiguous is the drawing by Adriana Szczerepa of a tearful figure with ironic word juxtaposition – HAPPY HAPPY all over the background. Christian Haywood writes about the purgatorial alienation in one’s own town produced by the limbo-land circumstances, in which the inhabitants are perceived as zombies and “time moves and nothing else does”. Thomas Gallimore Barker conveys well the anxious boredom of the times in his poem Boredom’s Edge: “With nothing else to do I watch ice cubes melt”, “Pricks on my skin making me feel as if blue-neck Flesh Flies/Orbit around the rings below my eyes”.

Sometimes the whole visceral fear of plague and death comes through and we are presented with memento mori such as one might find in the woodcuts of the Middle Ages or German Expressionism. Rebecca Raynor gives us surreal portrayals of a skull with a halo, a part skeleton with a jaw missing and a skull with an arrow through it. There’s a floral piece by Michelle Coyne which has a lovely water-colour blurriness. I include it here as a memento mori because it subtly addresses the transience of beauty.

Rebecca Raynor’s grand piano-shaped object in black and white has lots of eyes under it. The eye motif is repeated elsewhere: in a photograph by Costanza Musto someone wears a sleeping mask; one eye of a face is concealed in Akash Waqar Ali’s white flowers sequence; Amy Crozier has decorative shields over the eyes of the model; Kelly Quinzel and Jessie Stansby have absent eyes and we have the eye sockets in Rebecca Raynor’s skulls too. Conversely, Jessie Stansby’s ‘upside down’ illustration in blue and red has lots of eyes, and eyes also figure in the tender drawings of Adriana Szczerepa.

Mask wearing emphasises the eyes and the motif also reminds us of the phenomenon of people watching for potential breaches of hygiene and social distancing. Nathan Langman gives us a nice photograph of the sparse orderliness of the superstore queue punctuated by the linear austerity of modern commercial architecture but otherwise these social control issues are not overtly reflected in this collection.

For example, mask wearing is not much recorded, but concealment/revelation of parts of the body emerges as a theme. Costanza Musto has photographed belly, genital area, and upper thighs; a waist encircled by a crown; thighs, calves but no feet; underarm and one breast; the back view of a person with shower cap and one glove. Abbie Ozard presents a closeup of thighs framed by clothing and a finger pointing into a lavatory. One of the Kinsey suite of portraits shows a face masked by a microphone and one framed by thighs. Holly Bazley concentrates on elbows and lower leg. Sorrel Higgins gives us back views of a head. Even Connor Dixon’s horse’s head is only partially revealed. Hannah Foster has a triptych of clasped hands in surgical gloves, rendered more poignant by the embargo on touch. In another, predominantly black photograph, she has areas of dramatically lit domestic details – washing machine, floorboards, wires – and the bottom half of someone standing there. The eye searches to make a narrative of this potential domestic crisis.

There is visual drama elsewhere too. Red – the colour of emergency – is prevalent and so is black and white. Nathan Langman composes his photo of one person waiting, phone in hand, to click and collect, against the boldly red grid lines of interior commercial architecture. Lola Primrose balances light and dark tones in her nine photographs, some of which have a sense of careful staging. Sam Kuchvara’s screen shots are dramatically combined with areas of black. Jessie Stansby’s black and white expressionist illustration has eyes distorted into teardrops and someone taking a tee-shirt off to reveal breasts with faces. Carlos Baselga’s diptych of related zigzag shapes in deep colours is also dynamic and dramatic. A photograph in indigo blue by Abbie Ozard approaches abstraction: the lit areas do not quite clarify. This is the drama of scrutiny, of not knowing, until you realise it’s about the colour and that’s why the bluesy poem by Adriana Szczerepa is placed next to it.

Not much in the collection is overtly political and there are few images of the iconic objects of the pandemic. I have already dealt with the paucity of masks. Glove Story by Nerizza Cargill Thompson is an account of “government mandated lock-down health-walks” – feel the bureaucratic weight in those words? There are studies of ghost-like, carelessly disposed surgical gloves against various textural backgrounds – one of them a grid – highlighting the eco-threatening status of such items at the same time that they represent “the disregard for key-workers and resources and the lives lost”. Sam Broadbent photographs masked hero medics at work in an operating theatre, with background lighting as if on stage.

What else? Conner Dixon expresses disillusionment with inadequate and hypocritical leadership in crudely scratched white on black. The imagery is drawn from Wild West myths: those morality tales where the difference between “good” and “bad” was not blurred as in reality. There is a non-heroic man on a horse with short legs and the anger energy lingers in these drawings. From Charlie Brazier we have crudely written slogans of people on the march, again in black and white, with some red, and a black and white poster using crude, effective humour to admonish people for not putting their mask over their mouth. These represent the visual limits of political anger but Thomas Gallimore Barker’s poem, The Weight of Shoulders, acknowledges the appalling pressure of being a health worker: “each one sinks trying to keep the other afloat” and the visceral nature of their enclosed world of suffering.

I was struck by the combined use of word and image in some of the work and wondered if the individuality of hand-written words has become more aesthetically/emotionally satisfying in an age where lettering is standardised. A drawing by Osragli Elezi exploits both meanings of the word “tears” by writing RIPS AND TEARS IN SUNDAY BEST next to a garment decorated with torn stars. The background assertion of HAPPY creates an ironic contrast with the vulnerably tearful figure in one of Adriana Sczcerepa’s drawings. Mike Thorpe has wittily/ironically personified cocktails with saucy drawings and hand-written descriptions: “Miss Snowball Advocaat lemonade and lime juice with a creamy head”. Conner Dixon’s hand-written explanatory note about his photographs of two brothers adds a personal touch about sibling “telepathic synchronicity” which endorses the sense of balance in the tent photographs. Jessie Stansby writes about impermanence in her Garden of Eden design.

Not everything is about the pandemic. There is optimism, commercial confidence, decorative power, and colorific dynamism to be found in the more neutral pieces. Orange is the colour of optimism and “a little creative concept thought up by @livmard & @frederika_wd supported by @jamncollab>>” gives us a thematically coherent piece about oranges. Charlie Brazier asserts FUNKY. Frederica Davies’ blog entitled, “Conscious Consumption” is informative, tolerant, and responsible. Music journalist Camilla Whitfield decided to launch her online magazine Atomic Vox during lockdown and aims to showcase talented people. Laura Tobin’s elegant abstract design in coffee, caramel and cream encapsulates café culture; Emma Whiston’s jewelry in big, bold shapes exudes confidence. Sarah Hunter’s design of white clouds on a blue sky, Laura Tobin’s equally decorative painting of water with reflected light (appropriately juxtaposed with Estella Page’s get-away-from-it-all poem: Sail Away) and Faye Quinn’s cheerfully bright yellow and blue designs all evoke a glorious summer confidence. Hannah Whitlow’s collage of bright colours, which seem to float over the red/pink background, is vibrantly cheerful and there are even some jokes. Kaleigh Lowe’s “No Puffin” has a prohibition sign with a bird puffing a cigarette and Faye Quinn introduces Mr EGG “For a cracking meal”. Groan.

I have enjoyed seeing this compilation. It reflects the season of first wave Covid as having some mundane ordinariness, tedium even, in a sunny setting of edgy leisure and physical constraint, underpinned by anxiety, superstitious unease, and existential fear. At the same time, there is an enduring confident cheerfulness. I will end with Hannah Foster’s photograph of twilight through leaf-etched frosted glass. It is indeed the end of summer and darkness is descending but there are catches of golden and white light on the window.

Read a profile of Charlotte Rudd here.